The Unexamined Life: Patriotism

A Philosophical Inquiry into Loyalty, Land, and Identity in a Divided World

Brief Housekeeping

Welcome!

This will be the first of many in my new series of essays entitled 'The Unexamined Life.' The purpose of these Philosophical pieces is to deconstruct and examine seemingly everyday concepts to derive unexpected and useful meaning from them. They are intended to be both entertaining and, more importantly, educational.

These are for those inquiring minds who either enjoy delving deeper or feel they don't delve deep enough and wish to change that.

This piece, and the subsequent ones to follow in this series are shaping up to be far higher quality than my usual essays. What I am thinking is: I will one day make these my ‘paid subscriber exclusive’ content. So what I’m saying is, make the most of it whilst you can!

Acknowledging the extended length, and that I want those interested in more casual 2-5 minute reading to be able to enjoy my essays also, I have clearly segmented the essay into 7 manageable parts.

The chapters contained within this essay are as follows:

Chapter 1: Where we Belong

Chapter 2: What Do We Mean By Patriotism?

Chapter 3: Patriotism as a Justification of Death and Self Sacrifice

Chapter 4: Patriotism, Tribalism, and Modern Manifestations

Chapter 5: Patriotism Without Roots?

Chapter 6: Patriotism Without Borders?

Chapter 7: My Philosophy on Patriotism, and am I patriotic?

I thank you for taking the time to read if you go beyond this point, and I encourage you to stick around to the end, as this was a truly fascinating enquiry. What I conclude from it can be used by anyone to better there intellectual contribution to those around you as well as the greater world.

If you are already excited and ready to learn more about these brilliant topics worth deep diving, Subscribe for next week's essay on 'The Unexamined Mind.

But for now, housekeeping and shameless plugging aside, back to the all encompassing and ever elusive topic of, Patriotism.

"I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'"

— Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

CHAPTER 1

Where we Belong

Every nation, it seems, demands a willingness from its citizens to suffer – in hardship, in sacrifice, even in war – for its collective good. This unyielding allegiance, this 'patriotism,' is often celebrated blindly, yet few truly examine the invisible bonds that compel us to such devotion. Why do we champion a place simply because we happened to be born there? What is the true cost of this unexamined loyalty? And do we belong where we were born?

Picture this: You're driving through the sunny Highlands of Scotland in mid-summer. Your windows are down, and bagpipes hum melodically on the radio. A profound, awe-inspiring canvas of blue and green surrounds you, softened only slightly by a shimmering white mist weaving its way from peak to valley. Bonny sheep and shaggy cows roam free, from meadow to field, waterfall to river. Behind every mountain, a loch, a castle, or an ancient cottage waits.

This isn't just the country I belong to; This is me. It was 2014, and I was on a short road trip through the Highlands. Escaping to the Highlands once in a while is a necessity when you live in a city but are more accustomed to a rural setting. It's an exercise in remembering where I'm from, and what that truly means – it tends to give me a strong feeling of belonging, yes, but also strength. Oddly enough, this reminder drives me to want to do better, to make Scotland better.

I am, without a shadow of a doubt, very proud to be Scottish.

I think back on my road trips to the Highlands often, and very fondly, but this one stands out in particular. Those of you familiar with British politics will likely be aware that 2014 was the infamous year of the Scottish independence referendum.

A country at odds: half wanting Scottish independence, the other half wanting British solidarity. Scot on Scot, with England on the side-lines watching patiently, rubbing their hands together and licking their lips like a fat, hungry cat. This division created a palpable tension, manifest through action and gesture. On mountainsides, the words 'YES' or 'NO' were boldly proclaimed on massive white posters. These two defining words of 2014 for Scots could also be found carved into fields of flowers, grass, or wheat. Massive white banners wrapped around trees and buildings. Planes regularly flew banners emitting the same messages, leaving trails in the sky of either the Scottish or British flag. Not just this, but anything that could hold a sticker held hundreds, all saying the same thing: YES, or NO.

So there I was, arm hanging out the window, wind blowing through my hair, all the while trying to delve into that old, familiar feeling of 'I am a Scot'. But no matter how hard I tried – whether blasting bagpipes loudly, hiking a hill or mountain, or swimming in a loch or burn – I couldn't hold onto that feeling for long. I was dragged out of it every time I saw the word, NO. To me, it was nothing but a reminder that my country of Scots didn't want to be Scottish. It irked me, genuinely pained me even. I felt betrayed, or let down to some degree, like a football teammate who turns and shoots into your own goal after you've passed them the ball, leaving you with nothing to do but stand there, shoulders hunched, arms wide, saying, 'Eh?'

Regardless, I remained hopeful and had faith in my fellow countrymen that we would make the right decision.

It is now 2025. Eleven years on – Scotland is still not independent. Even now, a decade later, I still feel the sting of what felt like a tremendous loss for Scotland, like an old, awkward scar. But why? In the immediate aftermath, a bitter part of me wanted to rage at the perceived blindness, to accuse others of an almost wilful misunderstanding of Scotland's history, its economic realities, or the very implications of their vote. Did they truly comprehend what it meant to choose allegiance, or did they simply see themselves as Scottish while quietly accepting the status quo – perhaps even as 'England's bitch'? It felt, at times, as though deeply held affiliations were based on nothing more than inherited sentiment, never truly contemplated.

I remember, vividly, the jarring sight: Scots standing proudly by massive 'NO' signs, waving their Scottish flags with genuine joy. It was utterly absurd, profoundly striking. Like if a chicken proudly worked at KFC. It is so tempting to straw-man these individuals, to dismiss their choices as pure folly or a lack of conviction. But then, a more charitable thought emerges: perhaps, much like in sporting tournaments where you support a team that, if they win, helps your own team progress, some truly believed they were making the best tactical move for Scotland. There may well have been perceived ‘patriots’ voting 'No', genuinely believing Scotland would be better off not becoming independent.

And in a darkly humorous twist, their 'foresight' (and I suppose, 'mature' or 'tactical' voting) was, in hindsight, hilariously, tragically, wrong. The Scottish independence referendum on September 18, 2014, saw 55.3% of voters choose to remain part of the United Kingdom, while 44.7% voted for independence. Not long after, on June 23, 2016, another vote was held: Brexit. Britain voted, and Scotland almost entirely voted to stay, with 62% of Scottish voters opting to remain in the European Union, compared to 38% who voted to leave. Despite this, as a small part of Britain, our votes simply didn't matter. So we, like the rest of the UK, were pulled out against most of our will’s. After this, many who had voted 'No' in the original independence vote spoke out, admitting they had made the wrong choice. Eventually, Scotland pushed for another referendum, but this time... England said no. And it was too late. This entire saga, for me, remains both profoundly frustrating, frankly embarrassing and, yes, grimly amusing.

Had a second independence referendum been granted, public opinion has fluctuated significantly since 2014, with support for independence at its highest in 2020 and December 2022, sometimes peaking at 53% for 'Yes'. However, recent polls in late 2024 and early 2025 show support for independence often hovering around 40-50% (excluding undecided voters), with 'No' generally holding a narrow lead in many surveys. For instance, a YouGov poll in March 2025 indicated that 54% would vote 'No' to Scottish independence and 46% would vote 'Yes'. For me this just stands to prove a lack of coherent, strong, and confident opinions or world views. A large number of people are quite happy to shift with the herd when it suits or seems appealing.

Many of my friends and loved ones are often surprised to find out that I am a staunch patriot, or to some degree, a nationalist, as I frequently slander, mock, and criticize Scotland and those in it. For example, everytime I walk down Edinburgh high street and see the British flag flying higher than the Saltire, a long and jagged flow of expletives and finger wagging come from my general direction. Not aimed at the English/British, but at the Scots consciously making the decision to do this. What those close to me don't understand is that I hate out of love, but in the name of a dream—a country I someday want to see. I am critical because I want change.

However, this frustration does eventually give way to a more philosophically inquiring part of me. My personal experience in 2014, witnessing my country at odds with itself, underscored a deeper, universal truth: we often feel powerful allegiances without truly understanding their nature, sometimes leading us to make wacky and weird decisions. In my country's case, there is a split of allegiance. Those who are Scottish but identify more as British, and those who are, to put it bluntly, Real Scots. This enduring emotional echo compels us to look beyond the surface, to strip away assumptions, and confront that potent word: patriotism. To understand our place in a fractured world, and the loyalties we hold, we must first grapple with precisely what we mean when we invoke these invisible bonds. Questions that come to my mind now are, why do I feel this way about a clump of dirt? Why do I appear to hate that which I want to succeed, and Why do I feel the need to draw a distinction between perceived, and real, Scots?

CHAPTER 2

What Do We Mean By Patriotism?

For most, when a definition is required, we simply search Wikipedia, Google, an AI, or even a dictionary. I shall not be doing this here. Not to say this approach is wrong or bad, but it's simply not particularly useful in this case. It would be like boiling the kettle to toast the bread. It quite frankly doesn't provide us with what we're looking for when trying to understand something beyond its shiny wrapper. For yes, patriotism is a word, and yes, a dictionary definition will likely tell us its basic meaning, perhaps, 'an intense affiliation or inherent sense of belonging to a country or state'. And we know how to slot this word into a collection of others to create a seemingly coherent sentence, such as, 'Patriotism confuses me,' meaning, in context, 'people who have an intense affiliation or inherent sense of belonging to a country or state confuse me.' This is how language, and basic comprehension, works.

So, we are essentially starting from scratch. We have the word ‘patriotism’, sure, but besides that, nothing. It is merely a husk of a word, void of true meaning as of yet. Think of it as the cold, empty carcass of a word, one that we recognize and can sit on the shelf among all our other words. But it is yet to be filled with anything truly meaningful or potentially profound. The substance we fill these empty, yet usable, words with are what go into the concoctions of our ideas, worldviews, beliefs, and arguments, and are fundamentally what they are made from.

So, am I saying that language precedes things such as ideas and belief? That is a discussion for another time, in an essay I am, in fact, very interested in writing. For now, however, back to that patriotism thing.

Firstly, let me start with deconstructing a view that we can likely agree is globally accepted: Patriotism is love for one's country.

As previously outlined in the intro, I hate my country. However, I only hate it because I love it and want to see it be better. But I also hate that I have to love it in its current state. In fact, I hate that I feel I have to hate it, but I love that I hate it as to help it. Am I a patriot by the parameters of the proposition: Patriotism is love for one's country, then?

Yeeeee… I don't know. But I ‘think’ I am a Patriot.. So it must be the case, right?

Well let's take another proposition: To be 5’8 and under is to be considered short.

I am taller than 5’8, meaning by these parameters, I am not considered short. So am I short? Nnnnnn… I don't know. But I personally think I am not tall. So then, I ‘think’ it must be the case that I am short anyways.

Let us take a final proposition. If you are Human, you are a mammal.

By this proposition’s parameters, am I a mammal? Yes, it would appear that since I am indeed a human, I therefore too am a mammal.

Can you tell me the difference in the three propositions provided, and why this difference is significant?

To put it simply, all three appear to be a statement about reality, but their robustness and their very existence as 'truth-bearers' vary wildly.

Let us take the first proposal, ‘Patriotism is love for one's country’. What does this even mean? We have the word love: an infinitely complex and wide range of potential meanings and contradictions that, in my case, is at odds with hate, whilst also complementing it. And then there is the word country. What is that? Is it a geographical location, a political system, a cultural heritage? Both are hugely multi-faceted entities. So to then state X is Y for Z, but Y is not just Y, but, A, B, C, D, E. And Z is not just Z, but F, G, H, I, J. Meaning that X is now potentially A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J. Instead of narrowing on a meaning, it instead provides expanding potential meanings, thus provoking my earlier used phrase, ‘what does this even mean?’.

It would appear that logic is failed by this proposition, therefore, I shall move onto the next to explore its uniqueness.

The proposition, To be 5 '8 and under is to be considered short, seems like a black and white flow of logic at first. But then you realize that the word short is relative. For in this case, I explain that I am in fact taller than 5 '8, so by this measurement would not be considered short. But I myself do not see my height as one that is particularly tall. So in practice, I can say I am short, and a person who is 5’8 might then disagree, but someone who is 6’8 might agree. Definition in this case shifts with perspective.

Now, whereas the logic in this proposition can’t be said to have failed, its robustness when deployed alongside basic human nature and perspective does not hold up.

Finally then: If you are a Human, you are a mammal. This is logical and categorical, meaning it is based in fact—in this case, Biology. This proposition by extension then holds up of course to logic, and holds up for the most part against human nature and perspectives, as I am fully aware that there are still those of us who are convinced they are a parrot.

What then have these three seemingly simple statements taught us? Firstly, that a concept like 'patriotism,' built on inherently multifaceted terms like 'love' and 'country,' quickly unravels into a tapestry of infinite, unhelpful interpretations. It's a semantic quicksand. Secondly, even propositions with defined parameters, like height, can dissolve into a murky pool of subjective perception and relative meaning. And finally, we have the unyielding bedrock of objective truth, where 'human' necessarily entails 'mammal,' a truth impervious to personal whims. The striking disparity in robustness among these 'truth-bearers' illuminates the profound challenge we face with patriotism. It's not a neatly defined biological fact or a simple measurable quantity; it is a sprawling, often contradictory, and deeply personal phenomenon that resists easy encapsulation. This is why we cannot simply 'look up' what patriotism means – we must actively unearth it, dissect its many layers, and piece together a truer understanding.

This intellectual excavation leads us directly to the crucial distinctions that often define the very nature of national allegiance: Civic versus Ethnic Patriotism. These are not mere academic categories; they represent fundamentally different answers to the perennial question of 'who are we?' and 'what do we stand for?'

Consider Civic Patriotism, for instance, which you might liken to loyalty to a constitution, a set of laws, or even a shared dream. It's not about the bricks and mortar of the physical building, but the architectural principles it was built upon; it is the software of a nation, constantly updateable, rather than the hardware. This form of loyalty acts like a grand, inclusive banquet table, where anyone, regardless of their background, can pull up a chair so long as they respect the shared rules of civility and the values of the household. It fosters unity not through homogeneity, but through a shared commitment to a common political project – building a better society together. It actively invites self-critique, because the 'ideal' is always something to strive for, not a fixed, unblemished past. It encourages asking: 'Are we truly living up to our stated values of liberty and justice for all?'

Of course, some might scoff, claiming civic patriotism is a cold, intellectual construct, lacking the visceral, 'gut-level' emotional pull that truly binds people. However, while it may not immediately stir the primeval 'blood and soil' urges, its very strength lies in this reasoned rather than purely reactive foundation. Its adaptability is its superpower; like a flexible spine, it can bend without breaking. Its moral grounding acts as a built-in compass, steering it away from the perilous rocks of demagoguery and xenophobia. The emotional connection isn't absent; it simply flowers differently – a deep, abiding pride in the pursuit of justice, the defence of liberty, and the ongoing project of equality. One can cultivate a profound love for the idea of their nation, rather than just the accidental fact of their birth within its borders.

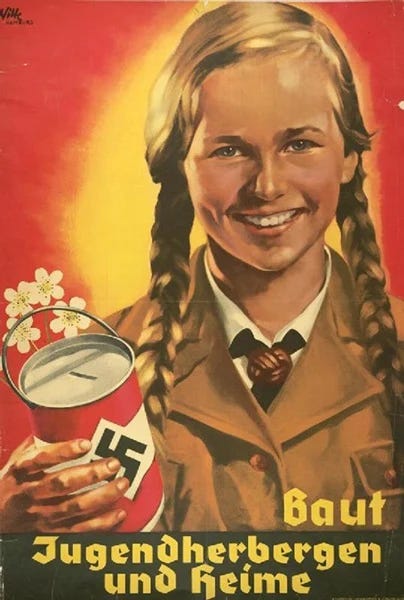

In stark contrast stands Ethnic Patriotism, often synonymous with a more problematic form of nationalism. This can be thought of as loyalty to your family tree, your ancestral village, or a secret handshake only those of a certain lineage know. It's about the hardware of a nation – its unchangeable, inherited components; it's about 'who we are because of where we came from and who our ancestors were.' This form of loyalty, while seemingly providing a strong, warm embrace for the 'insider,' does so by erecting high, often impenetrable walls against the 'outsider.' It's inherently exclusionary, breeding suspicion and fear of anything deemed 'other' – a fertile ground for xenophobia. Identity becomes a zero-sum game, where 'our' strength is defined by 'their' weakness. Rooted in the accidents of birth – where you were born, the language your parents spoke, the colour of your skin – it offers no moral compass for dealing with difference, frequently leading to conflict and oppression. It answers 'who are we?' with a backward-looking glance at lineage, rather than a forward-looking vision of shared purpose.

Proponents often champion it as providing a primal, almost tribal, 'natural' bond, arguing it’s the most potent force for unity and the essential guardian of unique cultural identities. Yet, while the desire for cultural preservation is a deeply human and valuable impulse – a vibrant tapestry woven through generations – it is a category error to inextricably link it to ethnic exclusivity or political loyalty. One can celebrate and nurture Scottish Gaelic culture, for instance, without demanding a purity of bloodline or excluding those who adopt it. Indeed, the most vibrant cultures are often those that evolve through exchange and embrace. When cultural preservation becomes synonymous with ethnic loyalty, it frequently devolves into the dangerous currents of racism, jingoism, and the oppression of minorities, sacrificing universal human dignity at the altar of a narrow, inherited identity.

The profound significance of these distinctions becomes painfully clear when we examine real-world scenarios. The debates surrounding American identity, for instance, often dance precariously on this very fault line. Was the initial surge of patriotism following 9/11 a civic rallying cry – a unity based on shared democratic values and a commitment to protecting the institutions of liberty, open to all who called the U.S. home, regardless of origin? Or did it, at times, lean into an ethnic sense of 'American-ness' defined by a perceived common heritage, an 'us vs. them' mentality against those not conforming to a narrow cultural archetype? Similarly, examining post-9/11 Afghanistan presents another complex case. Was the vision for a new Afghan state rooted in a civic desire for a specific set of democratic values and inclusive institutions, aimed at building a unified nation from diverse ethnic groups? Or did historical grievances and deeply ingrained tribal and ethnic loyalties ultimately overshadow this, making it challenging to forge a pan-Afghan civic identity? Understanding these distinctions is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for navigating the complex political landscape, for understanding historical trajectories, and for uncovering, understanding, and then advocating for a form of patriotism that is inclusive, just, and forward-looking in any nation.

CHAPTER 3

Patriotism as a Justification of Death and Self Sacrifice

The previous section, primarily focusing on the language used in this analysis of ‘Patriotism’, as well as two distinct versions of it, has brought us to a crucial crossroads: understanding that patriotism is far from a simple sentiment. We've seen how it bifurcates into two distinct paths – the inclusive, forward-looking ideal of Civic Patriotism, and the often exclusionary, backward-gazing reality of Ethnic Patriotism. But how do these profound, often hidden, distinctions ripple out into the visible world around us? How do they shape the very fabric of our national identities, influencing everything from the maps we draw to the songs we sing, and even the sacrifices we're willing to make? It's time to peel back another layer and explore the physical and cultural anchors that tether us to our nations. These are the symbols and narratives that, on the surface, seem to define who we are, but upon closer inspection, reveal a fascinating interplay of accident, choice, and deep-seated human needs.

Let's begin with the most fundamental and mostly unquestioned symbol of nationhood: the border. This invisible dictator of who is who, who gets what, and what is where, possesses a powerful yet unseen authority, dictating the lives of everyone on this planet. This abstract thing quite literally separates ‘us’ from ‘them’, attempting to convince us that one piece of land is inherently different to a piece just an inch over from it. I refer to it as a Deity, for it is my take that many borders, and the very idea of a border, are as ancient as some religious beliefs themselves. They can be seen as old standing, and as fundamental to the development of different global frameworks. It's interesting to focus on how a border can be viewed as potentially more fundamental to shaping the world we know today than religion itself. When you begin to think about it, you realise that it is these borders that segregate people, creating distinct populations within which unique cultural practices and religions often develop and become dominant. For instance, consider the historical division between the Roman Empire and tribal territories in Europe, which contributed to distinct cultural and eventually religious zones. Or, think about how the geographical isolation of ancient Egypt fostered a unique pantheon of gods, distinct from those in Mesopotamia, even though the regions were relatively close. Without these abstract lines, whether physical or societal, one could argue that some, if not most, religions would not have emerged in their specific forms, or at least other belief systems might have taken their place. Of course, I am aware that in saying this I am essentially claiming that if history was different, then so too would be the present, which is rather obvious. My point here, however, is not to delve into the complexities and intrigue of the butterfly effect, but instead to underscore where I feel borders come in the hierarchy of things that facilitate and constrain human and cultural dynamics.

One might then raise the point: haven't religions been the cause, or at least a large contributor, to many conflicts throughout human history, subsequently shifting land control and redrawing borders? While this is undeniably true – the Thirty Years' War in Europe, for example, was deeply intertwined with religious divides, and the partition of India in 1947 created new borders based on religious demographics, leading to immense conflict – my core argument still holds. The very existence of distinct religious identities, which then become grounds for conflict, is profoundly shaped by the pre-existing or emerging territorial divisions. Even if the religions themselves still existed in some form, the nature and scale of those conflicts might have been drastically different without the clear "lines in the sand" that define "our land" versus "their land." This is not to claim that no borders would equal no religions and no conflict, as this would definitely not be the case. Human nature is complex, and conflict has myriad sources. However, as a way of deconstructing what a border truly is, and understanding its profound capacity to organize and divide human societies, it serves as a crucial lens for understanding how it relates to patriotism and its potentially dangerous implications that we discussed in the previous section.

Thus, when we ask, "Why does an abstract line on a map define your allegiance?" The answer seems to become more complex. These lines are rarely pristine, natural divisions; instead, they are often historical accidents or the products of power struggles. Yet, we imbue them with immense, almost sacred, meaning, as if the very soil magically shifts its essence at these arbitrary demarcations. This suggests a powerful collective delusion or a deeply ingrained process of shared myth-making. The underlying reason for this phenomenon is that humans inherently seek order and identity, and these lines provide a seemingly clear boundary for "us" versus "them." They simplify a complex world into digestible, defendable territories.

Beyond these abstract lines on a map, there are the vibrant threads of culture that bind us. This leads one to ask, "Why do we identify with national dishes, instruments, dances, songs, and landmarks?" These aren't just random quirks of geography; they are chosen and cultivated symbols that actively create what the philosopher Benedict Anderson termed an "imagined community." They serve as tangible anchors for intangible shared stories and collective memories. We are, at our core, narrative creatures, understanding ourselves and our world through stories. Thus, these national symbols provide a common script and stage for the "national drama," allowing millions of strangers, who will never meet, to feel a profound, collective bond. (If you are interested in a deeper dive on the question ‘what is a story?’, you can read my other piece that tackles this here).

And then, flowing from the raw emotional power these symbols appear to have over us, comes the most profound question: "Why are people willing to die in war for these songs and dances?" It's rarely for the literal flag, the tune of a bagpipe, or a specific recipe. Instead, it would seem more reasonable to suppose that people are willing to make the ultimate sacrifice not for the literal symbols themselves, like charging into battle, claymore raised high above head with a kilt blowing in the wind, whilst screaming ‘FREEEDDOOOM’; all in the name of haggis. But instead for the abstract ideals and existential security those symbols represent: ‘freedom’, justice, the safety of family, the preservation of a homeland, or a way of life perceived to be under threat. This occurs because the national narrative, carefully constructed and reinforced, successfully convinces individuals that their personal fate, their future, and the well-being of their loved ones are inextricably linked to the fate of the nation itself. This makes the nation's struggle their struggle – transforming a collective problem into an intensely individual one.

Shifting then from the grand national stage to the quiet corners of our own minds, we must ask how this all translates personally: "How do you even know if you are patriotic?" Is it that butterfly-like sensation I get when I hear the sound of a lone piper playing ‘Flower of Scotland’, a feeling so profound it often brings a tear to my eye? If patriotism can be felt, where can this thing called patriotism actually be noticed so it can be identified? Where is patriotism even happening? If I were to point at it like I could with my foot, where would it be?

Patriotism doesn't appear to be something like an emotion itself, then again, where would you even point when asked to point at anger; instead, it often persists through them. For instance, I might feel sadness when my country isn't doing well, and happiness when it is. The real question then becomes, how do I know to relate this happiness or sadness to something that reliably indicates patriotism? Furthermore, how do I even know that I am truly happy or sad in such cases, rather than merely reacting to a carefully constructed narrative?

As discussed earlier, we are creatures of narrative, and our nation's very much take advantage of this fact through mechanisms like propaganda, or pervasive national myth-making. This can subtly, or sometimes overtly, skew our perceptions, takes, and feelings on certain decisions or realities. For example, if a government propagates a false narrative about an external threat to justify a war, the sadness or fear citizens feel, while genuine emotions, are rooted in a deception. This is not to say that to be sad as a consequence of, say, receiving bad news that is not known to you to be a lie, isn't truly sadness; it is a real emotional experience. However, I would argue that it isn't sadness based in truth, because the premise for the emotion is false. So, while you may be genuinely moved and emotionally affected, the underlying "truth" that provoked this response is, in fact, not the case. This crucial distinction means that genuine reconciliation or a change in emotional stance becomes possible if the truth were to be uncovered and accepted.

The logical trajectory here is critical: if our supposed patriotic sentiments can be manufactured or misdirected by narratives not grounded in reality, then these feelings, no matter how intense, cannot be the sole or primary determinant of genuine patriotism. To define patriotism purely by such potentially manipulated emotions would render the concept vulnerable to exploitation and divorced from any real commitment to the nation's actual well-being. To avoid the concept of patriotism to avoid being weaponized or purposed solely as a tool of control, It's a fundamental philosophical requirement that any "true" form of a concept must resist facile manipulation and instead be anchored in something more robust – in this case, truth and genuine concern for the object of that feeling.

Therefore, it would appear that some form of ‘true patriotism’, so to speak, isn't always about a grand, public declaration or flag-waving; it's often found in more subtle inclinations, quiet emotional responses, and habitual actions. It is a consistent, though perhaps unarticulated, commitment to the well-being and ideals of one's country, even to the point of fierce critique. Indeed, a critical patriot, one willing to challenge injustice, demand accountability, and strive for improvement, ultimately serves their country far better than someone who offers only blind, unquestioning allegiance. This active engagement is a deeper form of loyalty, born from truth and genuine concern, not manufactured sentiment.

However, a vital question immediately arises: "So, to be that which constantly critiques their nation is that which is patriotic?” This still doesn't sound right, however. This claim, or at least the current wording of it, appears to still assume an inherent love for one's country, and that this love is the sole reason for critique, aimed solely at national improvement. But what happens when such critiques are consistently ignored, or worse, suppressed? Does that love turn to hate? Does one remain patriotic in such a case, perhaps merely reminiscing about a land that once was, now hard-set on fundamentally altering, or even "abolishing," that which now is? This indeed seems an odd realisation: can you be patriotic and simultaneously desire to dismantle the very structure of your country?

This apparent contradiction highlights a critical distinction and a necessary refinement to our understanding of the "critical patriot." True patriotism, as we are defining it, isn't about blind affection for the status quo or an unyielding attachment to historical accidents. Instead, it is a principled commitment to a nation's foundational ideals – those underlying tenets of justice, liberty, equality, or collective welfare that define its best possible self. When these ideals are betrayed, or when the nation's actions fall woefully short of them, the critical patriot is compelled to speak out, not from a desire for destruction, but from a profound commitment to the idea of the nation. For example, American civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. were profoundly patriotic. They critiqued the systemic racism of their country not because they hated America, but precisely because they loved its stated ideals of liberty and justice, and fought to make the nation live up to those promises. Their critique was the purest form of loyalty.

The second, and perhaps more challenging, objection arises when considering the practical implications of such widespread critical patriotism. I think it best to be gone with the idea of the individual who is the critic is that who is truly patriotic in its truest sense, as this I find hard to be true, or if it is, disturbing. That, in my opinion, would be to claim that those who are truly patriotic can only ever be an outlier or minority, say, no more than 1% of a population surely. This brings us to a crucial point about national cohesion and the willingness to make ultimate sacrifices. As previously discussed, a country needs citizens willing to defend it if something such as a war occurs. It would appear evident that those highly critical and sceptical, perhaps more inclined to reason and analysis, might indeed be less willing to participate in conflicts, especially if they perceive the calls to arms as propaganda. What then would occur is a nation with no one willing to fight, despite a supposed love for said nation, potentially resulting in its forceful downfall. This indeed seems a deeply contradictory, even absurd, outcome.

However, this argument I have started to form it would seem rests on a false dichotomy between critical thinking and collective action, and between civic and ethnic loyalty. A critical patriot is not necessarily a pacifist or someone unwilling to defend their nation. Their loyalty is simply directed differently. Instead of fighting for a specific regime, a historical border, or a narrow ethnic identity, they fight for the ideals and institutions that underpin their concept of a just society. For example, during World War II, many American soldiers fought not just for a geographical landmass, but for the ideals of democracy, freedom, and against fascism – even if they simultaneously recognized and criticized racial segregation at home. Their critique did not diminish their willingness to fight for a better America. Similarly, a Scottish critical patriot might fight to defend the democratic institutions of Scotland, or the shared values of its society, even while fiercely campaigning for its independence from the UK, or critiquing its social policies. Their patriotism is for the potentiality and principles of the nation, not its flaws.

Furthermore, this doesn't relegate true patriotism to a tiny, isolated elite. Rather, it challenges societies to cultivate a broader civic understanding of patriotism. It posits that a truly strong nation is one whose citizens are engaged and critically aware, precisely because their loyalty is built on robust, defensible ideals rather than fragile, manipulated sentiments. While unquestioning obedience might offer short-term cohesion in certain circumstances, history is replete with examples where blind allegiance to false narratives led nations down destructive paths, often resulting in their eventual downfall or moral bankruptcy. A populace capable of critical analysis, even in moments of crisis, is ultimately more resilient and more likely to make choices that genuinely serve the nation's long-term well-being. It is, therefore, a claim that true strength lies not in suppressing dissent, but in fostering a patriotism that is robust enough to withstand, and even benefit from, honest critique.

This perspective on patriotism – one rooted in critical engagement and commitment to ideals rather than blind allegiance or inherited sentiment – fundamentally redefines loyalty. It moves beyond the simplistic "love it or leave it" mentality to embrace a more mature, discerning relationship with one's nation. This understanding is particularly illuminated when we finally ponder the role of sheer happenstance in our loyalties.

Consider the question: "If you got to choose where you were born, would you be more or less patriotic?" If patriotism were truly an innate, unchangeable trait, the idea of choice would be entirely irrelevant. The very fact that our patriotic sentiments could shift with a different birth location suggests a strong learned or conditioned component to our loyalty. This highlights the significant role that shared values, opportunities, and the adopted community play in fostering allegiance. We frequently observe this in the real world: migrants, for example, often display fierce patriotism to their adopted homelands, choosing allegiance based on the values and opportunities offered, powerfully demonstrating that patriotism isn't solely a birth right. While some might argue that a 'rootless' choice would somehow dilute "true" patriotism, making it merely transactional, this perspective misunderstands patriotism as purely genetic. In fact, when patriotism is actively chosen – a conscious commitment to a nation's ideals – it can be a deeply held and perhaps even stronger form of loyalty.

In essence, whether through inherent birth right or deliberate choice, a genuine and resilient patriotism emerges not from unthinking devotion to abstract borders or manipulated narratives, but from an informed, critical, and active commitment to the best version of one's nation. It is this nuanced understanding that truly addresses the complexities of a feeling that can inspire both profound sacrifice and dangerous folly, allowing us to move towards a more examined and ultimately more virtuous form of national loyalty.

CHAPTER 4

Patriotism, Tribalism, and Modern Manifestations

This journey into the unexamined life now compels us to ask: Is patriotism founded off of a more primitive instinct, in tribalism? There is indeed a strong argument for its origins in our innate drive for group cohesion and survival, writ large across human history. Evolutionary psychology suggests that an in-group preference provides fundamental safety, facilitates resource sharing within the group, and offers collective defence against perceived out-groups. Patriotism, in this light, appears to leverage these ancient, deeply ingrained mechanisms, simply scaling them up from the small tribe to the vast nation.

If patriotism taps into these primal group loyalties, then it logically follows that we would find outlets for these instincts even in seemingly benign modern activities. This leads us to ponder: Why do patriotism and sports fans seem so interlinked? Sports, in essence, offer a sublimated, ritualized, and relatively safe outlet for these tribalistic instincts. They provide a powerful "us vs. them" dynamic without the real-world consequences of actual conflict. The shared emotional highs of victory or the collective despair of defeat, the forging of a collective identity around a team, the presence of a common "enemy" in the opposing side, and the symbolic victories achieved on the field all powerfully reinforce that deep-seated tribal bond. It is in this arena that the national anthem, the flag, and the team's colours become highly charged symbols, capable of evoking intense, often irrational, loyalty and emotion.

However, like any powerful instinct, this primal patriotism is a double-edged sword. While these deep-seated group cohesion instincts foster unity and collective action, they are also the fertile ground for prejudice, xenophobia, and the dehumanization of "others." When unmitigated by reason, empathy, and universal values – the very cornerstones of the civic patriotism we discussed – this primal, unchecked patriotism can lead to aggression and historical atrocities. History unfortunately offers countless grim examples where such tribal loyalty, fueled by fear and suspicion of the 'other,' has paved the way for immense human suffering. Consider, for instance, the Rwandan Genocide of 1994. Here, a pre-existing ethnic division between Hutu and Tutsi was deliberately exacerbated by propagandists. Unquestioning tribal loyalty, cultivated for decades, became paramount. Radio broadcasts and political rhetoric relentlessly fueled fear and suspicion of the 'other', painting the Tutsi minority as an existential threat to the Hutu majority. This insidious process of dehumanization ultimately paved the way for the horrific slaughter of over 800,000 people in just 100 days. This serves as a stark, modern illustration of how deeply ingrained group instincts, when left unchecked and actively manipulated, can lead to the most extreme forms of violence and widespread suffering.

CHAPTER 5

Patriotism Without Roots?

Imagine a vast, uninhabited landmass. Let's call it, "The Genesis Continent". Alongside this continent, are many others, much like our planet. On these other continents are mixes of many civilisations. When a child is born, they are transported to the Genesis continent. These children are then stored in pods in a comatose state until the age of 16. Each teen is randomly assigned to a distinct "nation," and placed into different territories with no prior connection to their assigned group or land. Everyone is aware of this system, and every new teen is educated of this as early as they can comprehend it. This thought experiment is designed to strip away the accidental nature of birth-patriotism, forcing us to observe what might emerge when loyalty is entirely unrooted.

What happens to patriotism in such a world? Two compelling, yet seemingly contradictory, claims immediately present themselves. One might argue that a form of intense, immediate patriotism would emerge. After all, say you found yourself at 16 in this position, you would soon be made aware that everyone else is, to an extent, in the exact same position as you. I suppose in a sense this is similar to our state of affairs as of current. Regardless, this could act to bond you, and find connection or meaning. This is the deep human need for affiliation and identity to seek an immediate anchor in the assigned group. Social cohesion and survival within their new country would demand rapid adaptation and loyalty, creating a "cult-like" adherence to new symbols and narratives. Fear of being an outsider, or of simply being alone in an unknown world, would be a powerful motivator for this instant bonding. It then could be said that patriotism appears to be consequent not of the similarity of where one is born, but instead in a slight rephrasing, a similarity in the fact that we were all assigned an affiliation without choice. The shared feature in a lack of choice rather than the shared feature of a matching affiliation to a nation then could be grounds to identify patriotism by.

In stark contrast, another claim could be to suggest that a high percentage of these randomly assigned teenagers would attempt to defect. This perspective argues that if patriotism is partly about values alignment and affinity – a sense of shared purpose and genuine connection – then arbitrary assignment would inevitably lead to widespread misalignment. The inherent human desire for autonomy and self-determination would clash violently with an imposed, unchosen loyalty. In such a scenario, shared discontent could quickly form new, chosen "nations" from the disaffected, as individuals sought out communities that genuinely resonated with their inner selves. Or, they would potentially be outcast, excluded, killed, or even used as slaves; a painful pill to swallow, especially when holding up this ‘hypothetical’ reality and comparing it to the history of our own world, and realizing it isn't so hypothetical after all.

The philosophical implications of this Genesis Experiment, I feel, are rather interesting. This experiment powerfully suggests that while the need for belonging is primal, the form patriotism takes is highly constructed and deeply influenced by both the conditions of affiliation (assigned versus chosen) and the values of the group. It highlights the tension between the instinctive urge to belong and the rational or emotional need for alignment and affinity. Ultimately, this thought experiment makes a strong case for patriotism being less about where you're born and more about where your values and chosen community truly lie.

Having journeyed through the hypothetical plains of the Genesis Experiment, stripping away the accidental nature of birthright allegiance, we arrive at a compelling and perhaps even uncomfortable truth: if patriotism is indeed a matter of chosen values and affinity, rather than solely a primal instinct or a geographical lottery, then what does this imply for the future of loyalty? Does the very concept of patriotism, inextricably linked as it has been to borders and nation-states, face obsolescence in an increasingly interconnected world? Or can allegiance evolve beyond geographical confines? This profound question compels us to look forward, exploring the possibility of a patriotism that transcends the traditional boundaries we have always known.

CHAPTER 6

Patriotism Without Borders?

This leads directly to a crucial debate: Can you truly be patriotic without a country in the traditional sense? A compelling answer lies in the concept of cosmopolitan patriotism – a loyalty directed not at a physical landmass or a historical lineage, but at universal values such as justice, human rights, and democracy that transcend national borders. It is, in its most expansive form, possibly even a loyalty to the planet itself. It would seem to me that a healthy patriotism must be compatible with such a broader cosmopolitan outlook, recognizing our shared humanity. In a globally interconnected world, a narrow, exclusionary nationalism is increasingly maladaptive and dangerous, as global challenges like climate change, pandemics, and economic crises simply do not respect national boundaries.

However, some might argue that cosmopolitanism is a weak ideal, lacking the visceral emotional pull necessary to inspire collective action, or that it inevitably erodes vital local identities. This counter-argument, while understandable, misinterprets the very essence of this broader loyalty. Cosmopolitan patriotism is not about abandoning one's local or national identity; rather, it is about situating it within a larger moral framework. One can fiercely cherish Scottish culture, for instance, while simultaneously advocating for global human rights. True global challenges demand a global loyalty, understanding that the well-being of one's own community is inextricably linked to the well-being of the wider world.

This brings us to a foundational question for the nation-state itself: Can a country survive without conventionally patriotic citizens? Historically, no nation-state has successfully functioned or sustained itself without some form of widespread citizen loyalty. Patriotism, in its traditional sense, has been the vital fuel for civic engagement, the willingness to make collective sacrifices (such as paying taxes or participating in defence), and the bedrock of social cohesion. Without it, a shared sense of purpose would erode, potentially leading to fragmentation or, paradoxically, to authoritarian enforcement as a means of control. While an alternative take might suggest that perhaps global governance or entirely new forms of allegiance could eventually replace the nation-state and its traditional loyalties, such a shift remains, for now, a largely theoretical, perhaps utopian, goal. The emotional and historical weight of national identity is immense and profoundly resistant to rapid displacement.

Considering these complexities, I would like to argue that the only sustainable and ethical form of patriotism for the 21st century is a critical, civic, and cosmopolitan patriotism. This nuanced approach strikes a vital balance: it respects the fundamental human need for belonging and local identity while simultaneously upholding the moral imperative for inclusivity and global responsibility. It allows for a love of a country that is self-improving and outward-looking, grounded in truth and principles. Crucially, it's patriotism that actively encourages dissent when the country deviates from its ideals, rather than demanding blind loyalty. This, indeed, is the path forward for an unexamined patriotism to finally truly examine itself and evolve.

CHAPTER 7

My Philosophy on Patriotism, and am I patriotic?

This discourse into the mysterious labyrinth which is, abstract meaning, in this case, specific to patriotism, has been an interesting one. We began with a deceptively simple concept, only to discover a complex interplay of primitive instincts, cultural narratives, deeply personal experiences, and intricate political structures. From the invisible lines of borders to the powerful pull of shared stories, from the perils of unchecked tribalism to the promise of chosen loyalties, and of course one's potential desire to die for their country. We've dissected the very essence of what it means to belong.

From my own journey, spanning since arguably my birth, but here I will say 2014. The days where my dream of an independent Scotland was so close, yet simply not to be. And to the linguistic and cultural threads we've unravelled here now, I've come to embrace a vision of allegiance that is both deeply personal and universally expansive.

How I intend to go forward into the ever roaring arena which is, human existence on earth, is in a way which takes what I have thought about and considered here, and leverages it to better my contribution to those around me and the broader world.

This fairly long winded essay on the philosophy of patriotism has been an attempt at breaking down our every day understanding of what patriotism is, and slowly building it back up, understanding it in a new light. In other words, taking a blunt, shapeless rock from the ground, and fashioning an axe from it, a usable tool, so to fell trees and build shelter, or even fend off any would be attackers. My take here on patriotism appears to make the most sense, from what I can tell. It is one that can be seen as actionable, logical, and actually explainable.

And it is this:

True patriotism, it seems, is a profound and active desire for the flourishing of one's country, driven by a commitment to its highest ideals and a willingness to fiercely critique it when it falls short. This dedication, however, is tempered and ultimately strengthened by the crucial realization that the 21st century presents formidable threats—from climate change to pandemics—that transcend any national border. Therefore, in this interconnected world, supporting the collective well-being of humanity isn't a distraction from national loyalty, but it's very fulfilling. By championing universal values and fostering global cooperation, we don't dilute our love for our homeland; instead, we inadvertently create the conditions for a more secure, prosperous, and truly greater nation for all. It's this patriotism that understands that the healthiest roots reach not just deep into native soil, but also wide across the global garden.

This framework – a dynamic, critical, and chosen commitment to the evolving ideals and collective betterment of one's political community, understood within a broader humanistic and global responsibility – was forged directly from the insights gained in my life, and this essay. It arose from understanding the crucial distinctions between civic and ethnic patriotism, learning from the stark lessons of the Genesis experiment, acknowledging the powerful pull of our tribal roots, and recognizing the absolute necessity of a cosmopolitan outlook in our interconnected world. We can defend this framework for its resilience against manipulation, its firm ethical grounding, and its inherent capacity to adapt to a rapidly changing world. It fundamentally prioritizes values and shared principles over the arbitrary accident of origin. While the precise balance between local and global loyalties, or the exact degree of "emotional warmth" required, might always be subject to nuanced interpretation and messy application, I believe this philosophy offers the most promising path forward. It is a path towards unity without exclusion, identity without superiority, and a form of loyalty that genuinely serves humanity rather than dividing it. It is, in my view, the only patriotism compatible with a peaceful, just, global future, whilst also not simply being an empty dictionary definition.

A Husk instead of a Dream.

And that brings me to my final closing statement. Am I by definition, or I suppose more importantly, my new definition, patriotic?

Aye—and I will be for as long as the highlands are high, and the lowlands are low.

Yours in thoughtful inquiry,

Matthew.

What a ride. Thanks for sharing your insight. It’s hard to articulate loving something as abstract as a country. When you factor in culture and struggles and identity, it becomes difficult to describe just what makes you love it.

And there’s really no way to tell for sure if you would still love something if you weren’t raised with it. (Would religious scholars choose the same faith, had their parents not encouraged it?)

One thing you may find interesting:

In America, there’s a program called Boys State. Every year in every state, a host (1100 in my state) of 17 year old boys meets for a week and simulates running state government. I recently attended, and my experience reminds me largely of your Genesis Experiment.

When you arrive, you are randomly assigned into one of two political parties. These parties are just names; they have no established political agenda, figureheads, or meaning, other than the “us vs. them.” While it certainly wasn’t unanimous, (or a true controlled experimental environment) the loyalty I saw kids develop to their “party” was immediate and strong.

We quickly learned to identify with our party, and even though nobody knows each other and has no reason to ‘love’ their party, that’s exactly what happened. In fact, it quickly became extremely polarized.

We made chants around “beating the nationalists” and sweeping the podium, etc. (As quickly as we resorted to extremes, it’s unsurprising to see the current state of the American political system, but that’s neither here nor there.)

Anyway, in my personal experience, patriotism can indeed be formed without prior connection.

Thanks again for your thoughtful publication.