The Dignity Dilemma: Is Automation Liberating Our Purpose or Losing It?

Redefining Purpose in the Automated Age

"We are suffering, not from the rheumatics of old age, but from the growing-pains of over-rapid changes, from the pains of readjustment between one economic period and another."

— John Maynard Keynes

Who am I?

Starting of easy

Have you ever found yourself asking, "Who am I?" or “What can I do to make a difference?”

For those of us who are younger, these questions can be particularly challenging. It often requires a breadth of lived experience to provide a canvas clear enough for such a profound painting. An older person, perhaps sixty and upwards (sorry mum), often has a firmer grasp on their identity than someone like me, at the ripe old age of twenty-eight.

My grandpa, for instance, didn't really have the time for such deep existential musings. It seems he, and many others of his generation, already had an answer, if not the answer. They weren't told to discover it. They were simply told it. You were a farmer, a warehouse operative, a driver, a soldier, a doctor. Or, you were unemployed.

"The work is external to the worker... it is not his own work but work for someone else, that in it he does not belong to himself but to another."

— Karl Marx

In a world where many feel they are what they do, what does it mean to be unemployed? Does it imply you are nothing? Does one now rely on ancient proverbs, such as: You are what you eat? If so, rather worryingly, that would make me a Pretzel.

This brings us to a crucial concept: dignity. Knowing our purpose often provides us with dignity. The logic seems straightforward:

Job → Purpose → Dignity. This then begs the unsettling question:

Jobless → No Purpose → No Dignity? If current observations hold true – that those with employment tend to by extension feel even a minor sense of purpose – then a mass loss of employment and therefore purpose could indeed become problematic. Dignity, after all, is what empowers us to be active social agents.

“Who am I?—I am nothing.” No human should ever be tricked into believing in this great lie of lies, that something inside us so desperately would have us believe.

Who am I now?

The first humans to not be the smartest thing on earth

Automation, driven by AI and robotics, is poised to dramatically reshape our labour forces. Many propose Universal Basic Income (UBI) as a solution, arguing it can maintain quality of life and provide freedom. But does money equate to purpose? I would argue not. Can more free hours in the day simply generate purpose? For some, certainly, but I suspect it would fall victim to the Pareto Principle – the 80/20 rule. We often hear of billionaires proclaiming misery despite their riches, feeling they have nothing left to do. A cry for attention? Perhaps. But worth noticing? Definitely. My belief is that the coming era of mass job transformation will, by extension, cause a mass purpose crisis. This challenge could impact individuals globally, giving an unfortunately ironic meaning to the term 'equality'. This shift has already begun.

"The modern age... which began with such an unprecedented and promising outburst of human activity, may end in the deadliest, most sterile passivity history has ever known."

— Hannah Arendt

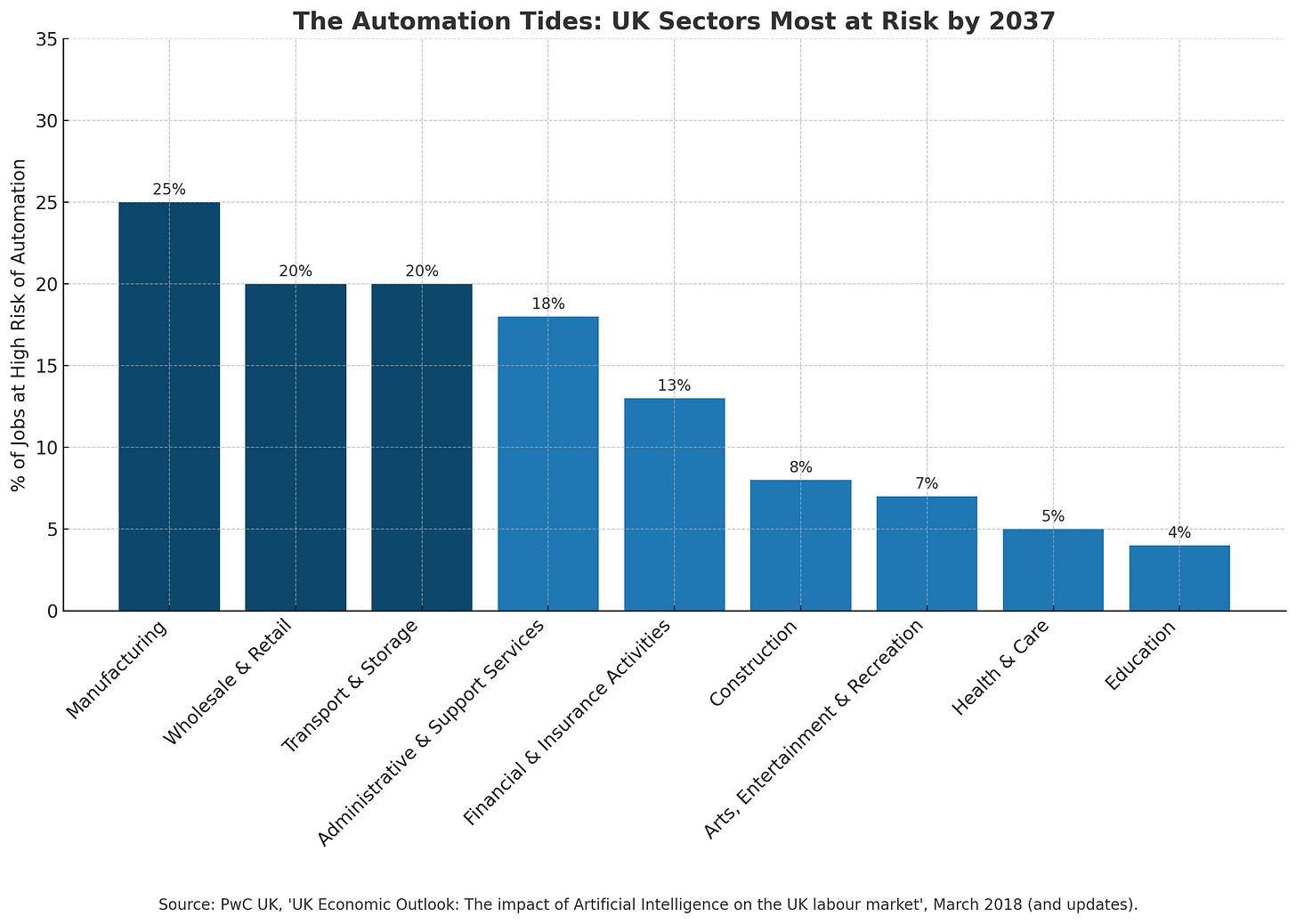

A 2018 data analysis from the UK, finding that manufacturing would be most at risk by 2037 with the information available at the time.

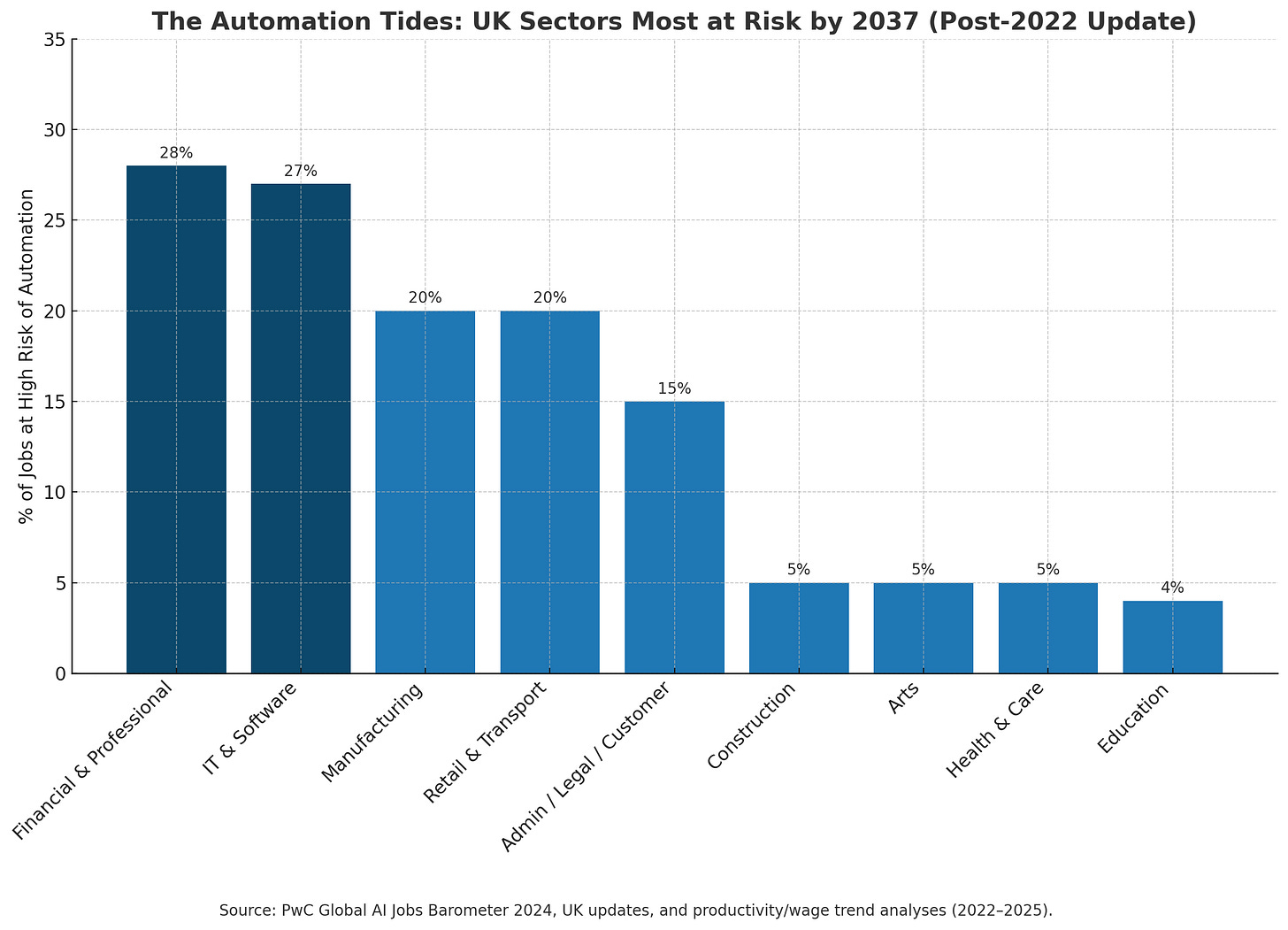

A second analysis also from the UK, however this time ranging from 2022 to today. As I am sure you have already noticed, we have a new contender for the most at risk in the job market as a result of automation.

The impact of automation is not merely theoretical; it's tangible and rapidly evolving. It's insightful to note that many people still assume automation primarily threatens traditional "low-skill" or "lower-class" jobs. This common misconception likely stems from easily visualised scenarios, like large robot arms performing multi-faceted tasks in warehouses. However, the real transformation is often less visible but far more pervasive. The latest data from the World Economic Forum (WEF) shows that automation, especially via generative AI, is profoundly reshaping the labor market across all sectors, extending far beyond low-skill roles to include cognitive, professional tasks. Many overlook the power of technologies already "beneath their noses".

Anyone who has experimented with a Large Language Model (LLM) like ChatGPT can attest to its efficiency in tasks that were once mundane and time-consuming. For example, these AIs can instantly sort vast collections of scattered information. This capability signals the beginning of significant disruption for financial, professional, IT, software, administrative, legal, and customer service roles. Tasks that once took teams of paralegals weeks to complete now take AI mere seconds. Indeed, the WEF highlights both job displacement and the emergence of new roles, stressing the critical need for new skills as analytical and creative thinking grow fastest.

"The current discourse... often implicitly assumes that low-skill, repetitive jobs are the primary targets, overlooking the growing capacity of AI to undertake complex cognitive tasks previously considered the sole preserve of human intelligence."

— "The Automation Paradox"

Lawyers aside, while “currently” lower on some risk charts, healthcare is also present. This suggests that in the coming decades, even highly skilled professionals like medical doctors may find their roles profoundly reshaped, if not made partially redundant. Given the vast shifts observed in job market predictions over just a few years, powered by advancements in AI, the question of who is "safe" becomes increasingly pertinent, especially with the future advent of quantum computing

(To get the down low on this little chestnut, you can read my piece on Quantum Ethics)

What I will say about a life of supposed freedom to do what one wishes, assuming this is done responsibly, I am confident that although many social issues will arise, as discussed, but too will great artists and creatives of all sorts begin to rise—a dawn of the next creative enlightenment so to speak. Men and Woman once subject to repetitively and monotony, subject to nothing but there will and a vast amount of time ahead of them to fill with whatever they can think of. The potential in my eyes are truly limitless.

"The man whose whole life is spent in performing a few simple operations... has no occasion to exert his understanding or to exercise his invention... He naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become."

— Adam Smith

How will I be remembered?

The stories we tell ourselves

So, do I see mass automation as a bad thing? No.

Can I see people living fulfilling lives in such a world? Yes.

Do I think a Universal Basic Income (UBI) will be required in the years to come? Yes.

Do I see this solving all of our varying societal and cultural problems as a result of mass job transformation? No.

Do I think it likely that there will be a rise in things such as mental health problems, anti-social behaviour, and a growing divide in wealth between the 1% and the rest? Yes.

So, what can be proactively done to mitigate the impact of automation, not just on our wallets, but on our minds and hearts? This, I argue, should be our focal point, especially given that UBI is already a popular concept being "tossed around like candy."

"The studies that have been conducted on this concept show that people who don't have to worry about where they are going to sleep or where their next meal is coming from start to think about educating themselves and finding worthwhile work."

— Rutger Bregman

From what I discussed earlier, it appears people often identify with what they do. This helps orient them in a large society filled with a diverse mix of people. After all, we all like to think we are making a difference, right? Take that away, and what is the motivation to even get out of bed? You might no longer worry about your children's or grandchildren's futures, as basic needs could theoretically be taken care of by automated systems. But then comes the stories we like to tell our selves, "What will they (descendants) think of me?" We reflect on the life stories of our elders, typically filled with hardship and toil to give our generation the lives we enjoy today, and we respect that. Will our generation have anything similarly meaningful to be remembered for? Imagine the conversation: "Hey, what did your grandpa do!?" "Oh, he doesn't say much, but I know he played a hell of a lot of video games!" "Nice! Mine said he did that for a while but then just read all his life!". Allot of us I imagine strive to be remembered as someone who done something, and the stories we tell ourself to guide our paths, deduce an ending that we can be proud of. I think it is our inherit nature to want to be remembered to some extent—for better typically, not for worse.

"The danger of the animal laborans is that it has nowhere to go once it is freed from the compulsion of labor."

— Hannah Arendt,

My Grandpa, John

A life of Big things, and Little things

My Grandpa was a Black Watch operative (the Scottish special forces) during 'The Great War'. He endured unimaginable training and fought for his country.

Upon his return, he joined the merchant navy and travelled the world, his ship regularly catching stray bullets from militias who had "bones to pick with the Brits".

After this, he came home to Scotland, to Fife, and worked in the mines for the rest of his life to be able to provide for his wife and five children. One of them, my father, managed to eventually scrape by into university, the first in our family to ever do so.

I just learned the other day that my Grandpa has recently been diagnosed with dementia, and every single one of us in my family (a fairly large family) have stepped up to support this man. Is it because that’s just what families do, or do we genuinely feel like we owe him? For he is a man who knew his purpose, and because of that purpose, I, and people I love are here now.

One might say, "Don't you think it would have been better for him if a lot of this time and suffering was saved by having robots fight our wars, deliver our exports, and acquire our natural resources?" To which, on his behalf, I would tell them, "I wouldn't change a thing," as I fondly recount him telling me as a child.

That isn’t to say that the world will not be more prosperous to have machines do that which is very difficult, and with little financial gain to the worker. But what I am learning as I get a little older, and what anyone my Grandpas age will tell you, it very much seems to be all the little things in-between these big things, like jobs, that make the, ‘big things’, worth doing in the first place. But, and this is a big BUT, it appears to be the big things, the hard things, or the otherwise interpreted, “bad things”, that makes you realise when you have truly found a “good thing”. You are only capable of distinguishing true good from the clutter of day to day life, when you yourself have experienced the truly bad. I know very little, but this much I know to be true.

If it weren’t for his very specific past, would he have ever met my grandma at a dinky wee jazz dance club on a faithful Saturday evening? Would he have the family that loves and supports him today when he will soon be needing it most? There is much you can say about my Grandpa, and much you cant. Like he never made allot of money, he wasn’t famous or influential in any way, he didnt change the world, nor did he write any books or memoirs (he is illiterate!)—what he did do however, was try.

"The free development of each is the condition for the free development of all."

— Karl Marx

We are Human

Dealing with an un-Human problem

This is a profoundly un-human problem, in need of a very human solution. The most promising solution I've encountered, which has in fact been discussed for a very long time (even before the invention of computers), is the redefinition of 'work' or 'job' to encompass different gains beyond financial wealth. Thinkers like Estlund (2017) and De Stefano (2018) emphasize the importance of work for social integration and personal fulfilment, advocating for broader definitions that include care, civic, and voluntary activities. This aligns with the argument that the non-monetary benefits of work—social connection, identity, and fulfilment—become critical as machines usurp routine tasks.

"The morality of work is the morality of slaves, and the modern world has no need of slavery."

— Bertrand Russell

The question before us, then, is not whether automation will reshape our world, but how we, as a society, will define purpose and dignity in its wake. It is a challenge that calls for profound philosophical reflection and proactive societal adaptation.

Is being entirely present for our children, with no late nights at work or important week long work trips going to be the new measure of purpose? Likely, it will be one of them. The old realities of what it is to be unemployed—a mostly shunned and cardinal sign of laziness, uselessness and anti-authority will be one of our potentially best contenders to sit on the thrown of that which gives us purpose.

Or, maybe I can just be a pretzel.

Change like this is not made over night, whereas advancements in automation make leaps and bounds every waking minute.

The story I tell myself

Trying

Perhaps some morsel of purpose can later be scraped up for my generation. Some great, great, great grandkid of mine manages to look back (likely through the powers of AI), and finds out who I was. They look through my entire life and realise, ‘He was one of them first ones who staired boundless intelligence straight in the face, right when it mattered most”. there annoying little friend no doubt replies, “But did they not loose? They missed there chance to do what was right?”, at which point I would like to think this wee descendent of mine will be able to read a little further down, and find himself met by an array of feats, perhaps resulting in no meaningful end, but enough at least to elicit his next words being—‘True, but hear it says, he tried.’

Here’s to purpose, here’s to trying, and here’s to not being what we eat.

Yours in thoughtful inquiry,

Matthew.

One of the best posts I've read today, Matthew! I loved how it takes off with "In a world where many feel they are what they do, what does it mean to be unemployed?"

So, I think I would say a couple of things from the perspective of Human Loops.

First, AI is already/going to be a massive global, structural, economic change, a true paradigm shift, that affects everything downstream of it, which will be A LOT, including incomes, jobs, businesses and economies, and then of course families, friends, status and connections at the relationships level (which is also pretty structural from an individual's perspective).

I'm sorry to hear about your grandad's dementia. That's a really tough one. His and your family's story is a great example from a past generation of previous structures, purposes and relationships that did all work together—for as long as they lasted. Now a lot of them are going to get trashed and what do you do with all the memories? How do we create new ones or generate or build better or acceptable options for our kids in their lives? And we know what happened to the mines and with de-industrialisation in the UK and all of the generational, social and family turmoil that caused.

Lots of people talk about UBI as the "obvious" solution but even if governments go for it on a big enough scale, how are they (ultimately we) supposed to pay for it all? Even more never-ending public debt and deficit spending? At some point, the labour-capital-consumer equilibrium modern economies are based on falls apart, even if the credit-debt part holds that long, because if enough jobs go, there won't be enough people with enough spare money to buy all the stuff the AI and the robots are producing.

Second, even if we can create social or economic gaps or pauses while we work it out, and work something temporary out for the money side, there is going to be a giant crisis of meaning that will affect all of the key institutions since the Enlightenment and represent an ontological challenge to human creativity and meaning themselves. We could introduce or hope for some positive greater spiritual evolution there, but how many people will just be mostly content to take the UBI and watch some more Netflix? And if everybody is getting lots of free income, what happens to prices and inflation for all of the stuff most people need in some form (housing, good, clothing, etc)?

Essentially, how do whole societies rebuild logistics and income structures for their actual families when a massive percentage of modern work is now threatened by AI? And let's remember that 99.9% of normal societies are not enthusiastic tech VCs in San Francisco or New York.